The adidas Sport Eyewear Fall/Winter 2025/26 Collection pushes the boundaries of sport-driven design, blending cutting-edge technology, elevated aesthetics, and uncompromising comfort.

Built for athletes and sport…

The adidas Sport Eyewear Fall/Winter 2025/26 Collection pushes the boundaries of sport-driven design, blending cutting-edge technology, elevated aesthetics, and uncompromising comfort.

Built for athletes and sport…

Across the billions of galaxies and stars in the Universe, only one place is…

A “gamechanging” injection to prevent HIV is set to be approved for use in England and Wales.

The long-acting jab, administered every two months, will offer an alternative to the daily pills used to protect against the virus.

This form of HIV…

Ferrari has cut the number of cars it sells in the UK as wealthy individuals relocate overseas after tax changes and the abolition of non-dom status.

The Italian luxury carmaker reportedly began limiting the number of vehicles it exported to the UK about six months ago, in an attempt to stop a decline in their residual value.

Benedetto Vigna, the chief executive of the carmaker, said that Ferrari had seen a “stabilisation” in sales after the decision to reduce the number of vehicles it allocated to the UK.

“Some people are getting out of that country for tax reasons,” he told the Financial Times, adding that taxes were not the only reason for the fall in residual values. “There are many different factors. Maybe when you sell to the UK, that car cannot be sold somewhere else [because of its right-hand wheel]”.

In April the government abolished favourable tax treatment for non-domiciled residents – UK residents who declared that their long-term home was overseas to avoid paying UK taxes on global income and assets – and raised other duties on the wealthy.

The chancellor, Rachel Reeves, told the Guardian earlier this week that talk of an exodus of wealthy residents was just “scaremongering”.

“This is a brilliant country and people want to live here,” she said. “And I think, when people scaremonger again this year, we should take some of that with a pinch of salt.”

Reeves, who has said that the wealthy will be one of the targets for higher taxes in next month’s budget, has previously ruled out imposing a “wealth tax” but campaigners for changes to the system have highlighted other options.

These include raising the rate of capital gains tax, levying national insurance on rental income and on partners in law firms and consultancies, and creating higher council tax bands.

The non-dom tax changes sparked fears that Ferrari would lose its wealthy client base, leading to volatility in its residual prices, or the expected secondhand value of a vehicle when a leasing deal comes to an end.

Most new cars in developed markets are bought on deals that provide financing based on the amount of value a vehicle loses – its “depreciation” – rather than the overall sticker price.

after newsletter promotion

If cars have weaker secondhand prices, the financing needed increases and the car becomes more expensive to lease.

The residual value for Ferrari’s Purosangue model fell 12.2% between January and October, while the SF90 Stradale fell 6.6%, according to AutoTrader.

However, prices have started to stabilise in recent months. The Ferrari 296 GTB, a supercar launched in 2022, had a recommended retail price from £256,275 if bought new. However, a used version was available from £189,490 on AutoTrader.

Pokemon Legends ZA is out, and the game is filled with plenty of Megas, which are insanely strong. For the first time in the series, wild Pokemon can Mega Evolve on their own, and the wildest part is that they can KO your creature before…

Under Paris’s autumn skies, the French capital came alive during the Vredestein 20 km de Paris from Oct. 10-12. Samsung hosted multiple pop-up experiences like a Street League Skateboarding…

When Beverly Glenn-Copeland was diagnosed with a form of dementia called Late two years ago, he was advised to stay at home and do crossword puzzles. He tried, but he doesn’t like crosswords, and it didn’t feel right. One day, recalls his…

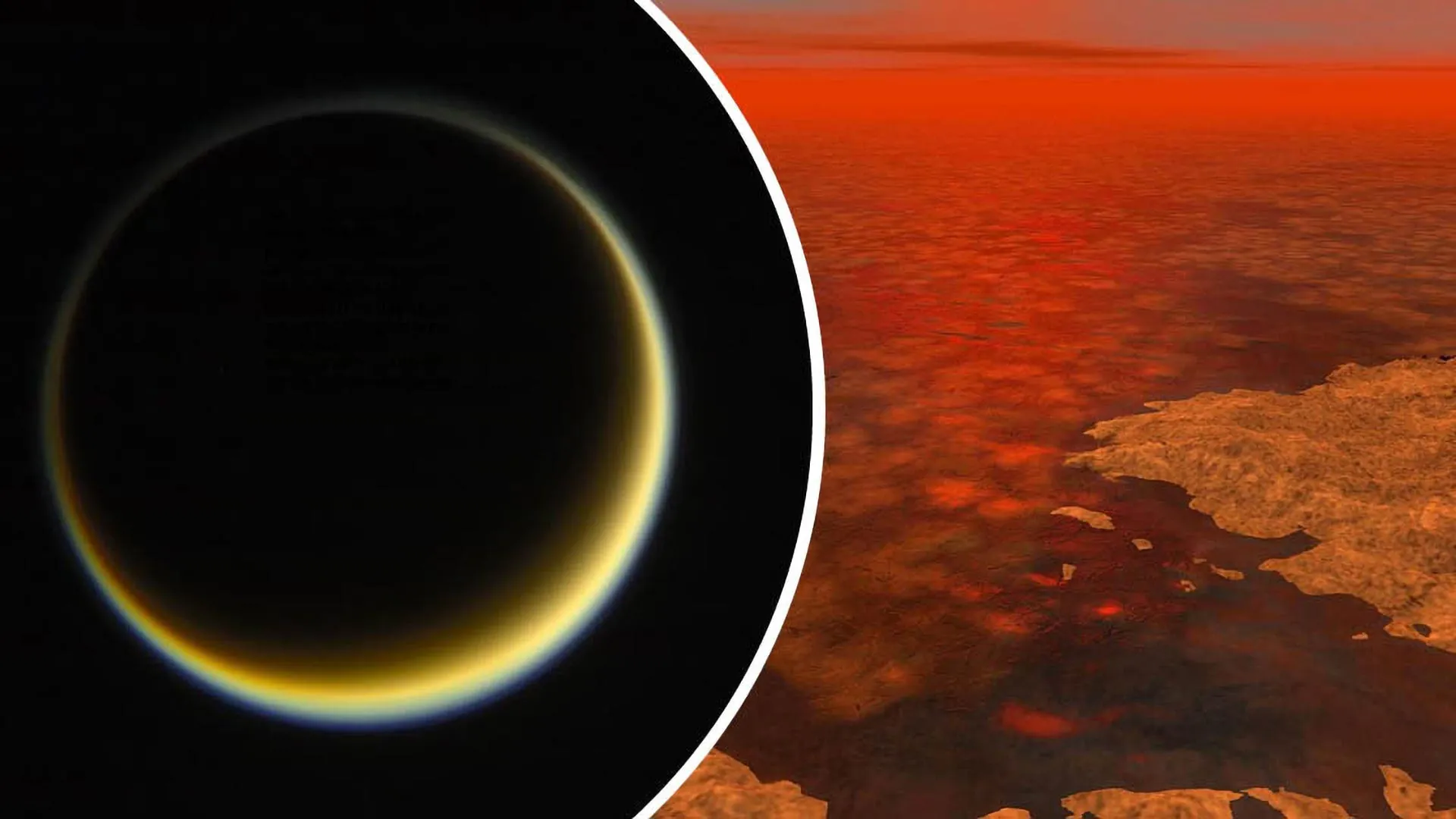

Scientists from Chalmers University of Technology in Sweden and NASA have made a surprising discovery that challenges one of chemistry’s fundamental principles, while also offering new insight into Saturn’s mysterious moon Titan. In Titan’s…

As Jim Chalmers moves among the global elite during the G20 talkfest with fellow finance ministers and big-time investors in Washington this week, he will be spruiking Australia’s enviable economic performance over recent years.

A particular point of pride has been the strength of the labour market.

Not only has unemployment stayed low, the increase in the share of working-age Australians with a job has climbed by 3.1 percentage points since immediately before the pandemic.

That increase is twice the OECD average, and compares with zero growth in the US and New Zealand. In Canada and the UK, the employment rates have dropped by 0.4 and 1.1 percentage points, respectively.

That performance, however, was cast under a cloud this week, after the unemployment rate unexpectedly jumped to 4.5% – its highest level in nearly four years.

After dropping to nearly 50-year lows of 3.4% in late 2022, the Reserve Bank of Australia and Treasury had both expected this rising trend to stop at about 4.3%.

The AMP chief economist, Shane Oliver, says that the jobless rate is “in a clear rising trend”.

Sign up: AU Breaking News email

The RBA board has made it clear it is holding fire on further rate cuts until it is more confident that inflation continued to ease through the September quarter. But the latest labour data has complicated the issue.

“A further rise beyond this would arguably be violating the RBA’s full employment objective,” Oliver says.

“Of course, the rise in unemployment may just reflect the lagged impact of weak economic growth last year, but it may also reflect a messy handover from the public sector to the private sector as the key driver of jobs.”

This “messy” handover is what has experts worried.

Big increases in federal funding for the care economy – from aged care, to childcare and health more broadly – flowed through to a surge in hiring that accounted for a lion’s share of the more than 1 million jobs created since Labor took office in 2022.

In the 2023 and 2024 calendar years, around 80-90% of the rise in employment was in these so-called “non-market” segments, or heavily taxpayer-subsidised industries.

That’s not to denigrate the roles.

As Chalmers has been quick to point out, “they are real jobs”.

“They look like real jobs to me, looking after older people and people in the NDIS and early childhood education,” he said last month.

after newsletter promotion

But this dynamic is key to understanding why employment could continue to boom even as the economy virtually stagnated.

Now we have, as Oliver says, the “messy handover”, as the private sector attempts to pick up the hiring slack.

Pat Bustamante, an economist at Westpac, calculates unemployment could push towards 4.8% in early 2026 if the private sector does not grow fast enough to replace the slower growth in government spending.

Which way it goes from here remains highly uncertain, and economists now see a real chance the RBA feels the need to deliver an interest rate cut at its Melbourne Cup day meeting.

Not everyone is convinced the jobs market is about to head south, or that the central bank will rush to cut rates again.

Jonathan Kearns is chief economist at Challenger and a former senior RBA official.

Kearns reckons people and investors have overreacted to one bad employment number.

Employment climbed in September, he says, just not quite as much as expected, which, when combined with an influx of new jobseekers, pushed up the jobless measure.

That could easily reverse in October, and the RBA board is likely to remain fixed on the “critical” quarterly inflation figure on 29 October.

“Things have been too easy,” Kearns says. “Inflation came down faster than expected and unemployment didn’t rise as much as anticipated. Things looked amazingly good, and you are always going to hit some bumps in the road.”

Patrick Commins is Guardian Australia’s economics editor